The Roehampton Human Rights Film Festival was the first professional project I had to realize at school. I learned a lot from this experience and particularly from team work. From a retrospective look, I am now able to analyze the whole process and to give some pieces of advice if a new festival is organized one day.

We started with the establishment of a program. We needed to choose which human rights issues the festival will cover. That involved understanding the meaning of human rights. It is a concept, described in Human Rights Declaration as «inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being ». In reality, this definition covers a multitude of areas including women’s rights, children’s rights, integrity rights, refugee’s rights, political, civil, social, economic, cultural rights….

This definition is constantly challenged. Its universalism had been questioned by the philosopher Joaquin Herrera Flores [1] . He describes human rights as a western influenced concept, defined with capitalist values while it should be applied to everyone, and be independent from cultural criteria.

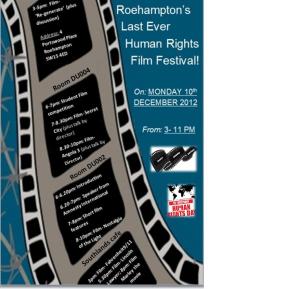

Human Rights issues are so numerous, and even environmental issues are taken into account by some festivals. We had to limit our choice to a certain issue in order to stay coherent. .Finally, our program was heteroclite. Our main aim was to give people clues to help them understand what ‘human rights’ means. We had to interrogate the audience about their own vision. The student competition shew us how the human rights conceptions are different from one person to another.

In Human rights Film festival: Global/Local networks for advocacy, Mariagiulia Grassilli [2] explains that Human Rights festivals ‘aim is ‘to build awareness.’ Like others, we had special guests, speakers and directors to intervene during our festival. That’s why I talked about coherence; in fact, everything went in the same direction. We all wanted to transmit and to receive knowledge about Human Rights.

‘Film can be a particularly powerful medium for human rights education , but again it is important to ensure that a human rights film festival ,for example , has a combination of ‘good news’ and ‘bad news’ messages and also that avenues are provided for people who wish to take further action’.

(Jim Ife: 2009)

Documentaries were numerous in our festival. Usually documentaries are considered as educational tools. They contain the power of cinema in itself. It is called ‘mimetic power’, a term coming from ‘mimesis’ which implies that the cinema reproduces natural mechanisms to perfection. The spectator recognizes himself and his environment in film and this process of identification is used to give people the inspiration to act by themselves. In Human Rights film festivals, documentaries are chosen because their relation to Truth makes them look more reliable to audience, and more likely to provoke a reaction. There is the idea that the movies and consequently, film festivals have an action in time, which lasts longer than the festival itself.

We, as members of the team, were confronted to this expectation from the audience. We were expected to provide reliable sources of information and movies of quality. I realized, as a floor manager, that people relies on us to give some information about the films. We were guarantor of Truth .If people asked us some questions I assume that it was because the films we programmed touched them. We had this impression for Nostalgia for the Light, but also because we were a part of an institution which provides an access to culture and education. We offered people an opportunity to watch marginal films and to be told about human rights issues to a ‘personal level’ throughout films.

‘The creators of the festival were seeking to raise awareness about human rights issues in a way that Human Rights Watch’s research and reports could not — in a way that spoke to people on an emotional and personal level as well as on an intellectual and political level. Film is above all about storytelling ‘

(Andrea Holley, deputy director of Human Rights Watch Film Festival)

Did we successfully reach this aim?

Amnesty international intervention was a good tool. The Q&A’s with Michael Chanan, director of Secret City as well, because both set interactivity between audience and festival’s actors .Thanks to them, Roehampton Human Rights Film Festival became ‘a place’, literally and figuratively, to share knowledge and opinions. This day, it was the gathering point of people’s networks.

Unfortunately, the efforts we put in publicity were not sufficient and we were disappointed about the number of people who turned out. I learned that students constitute a difficult audience to attract because they are constantly solicited. The same night, a great party was organized and we certainly suffered from its popularity.

To conclude I would say that this festival was a great opportunity to develop professional skills. But I only realize now, that building this festival will not have been possible without Human Rights.

Right to assembly,

Right to education

Right to choose and express freely,

Right to share our community’s art and science

…

[1] Marcelo Figueirido, The Universal Nature of Human Rights : The Brazilian Stance within Latin America’s scenario, The Universalim of Human Rights , Arnold Rainer Springer Editions

[2] Mariagiulia Grassilli , 2012, ‘Human rights Film festival: Global/Local networks for advocacy’, Film Festival YearBook 4 : Film Festivals and Activism, Edinburgh St Andrews Film Studies

Marcia G.Yerman,’Human Rights Watch Film Festival: An Interview with Andrea Holley’, Huffington Post.com

Cindy Hing-Yuk Wong, 2011, ‘Festivals as Public Sphere’, Film Festivals: Culture, People and Power on the Global Screen

Jim Ife, 2009, Human Rights from below : achieving rights from community development, Cambridge University Press